Advection fog develops as a result of a mass of warm air, with a high relative humidity value, moving horizontally (hence the term advection) over a cooler surface, whose temperature is below the dew-point temperature of the air.

When, as a result of conduction aided by turbulence, the air is cooled below its dew-point temperature, water vapour condenses, the water droplets producing the mist fog condition. This type of fog forms and persists under a wide range of wind speeds. The degree of turbulence dictates the maximum height to which the air is cooled, the height increasing with increasing wind speed. Thus the temperature gradient between air and surface in conjunction with the degree of turbulence determines the likelihood of advection fog. Low wind speeds provide more favorable conditions but, with a steep temperature gradient, advection fog can develop in gale force winds. However, higher wind speeds associated with small temperature gradients are more likely to produce low level stratus cloud, as the effective cooling of the air by the surface is less and is spread over a greater height. The atmosphere normally becomes stable since cooling of the air decreases the environmental lapse rate.

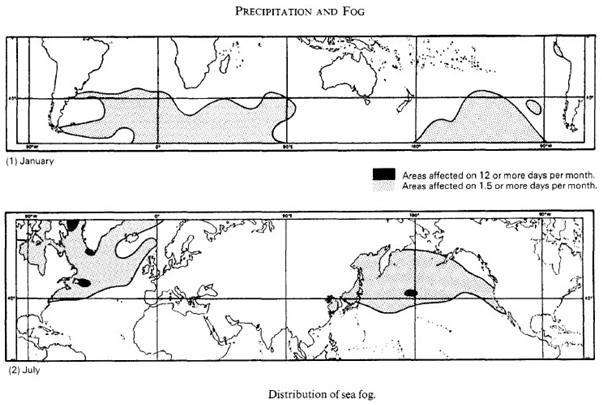

At sea advection fog, termed sea fog, occurs at certain times of the year. In northern latitudes, the Grand Banks of Newfoundland and the North Pacific zones are notorious particularly in July, when warm air from the south-west and south pass over the cold waters of the Labrador, and the Oyo Shio or Aleutian Currents respectively. Sea fog in these areas can persist for extended periods and will only disperse when either the wind speed increases, or its direction changes. Sea fog also occurs in lower latitudes during the summer in the region of the cold California, Canary, Peru and Benguela Currents.

Sea fog not only develops where cold currents exist, but also where there are favourable conditions of wind speed, air and sea surface temperatures. Examples are the spring and early summer fogs of the Western Approaches to the British Isles, where the south-westerly warm air stream from the Azores moves over the sea which, at this time of the year, is at its lowest temperature (Plates 21,22 and 23). In the North Sea, sea fog develops during the summer when warm north-east, east and sometimes southeasterly winds from Europe pass over the colder sea surface. Along the east coast of the British Isles this sea fog is called hoar or sea fret.

On land, warm air moving over cold surfaces may also produce advection fog. In the British Isles this usually occurs in winter through advection of a warm air stream from the Azores. At this time of year

Advection fog also develops over the southern and eastern areas of the United States of America, when warm air is advected from the Gulf of Mexico and the Bermuda region.

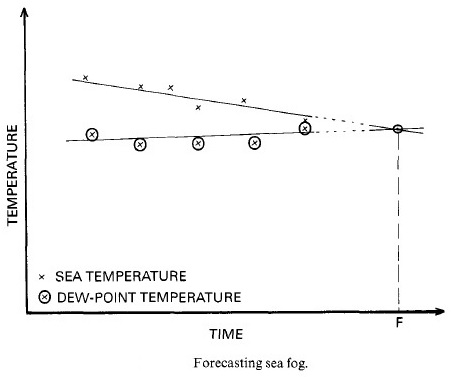

Sea fog is a frequent threat to the seafarer and its prediction is therefore important. As sea and dew point temperatures are critical in its formation, their observation at frequent intervals is recommended, and should be recorded in graphical form . By drawing straight lines to establish the trend of each temperature, it is possible to determine the point of intersection (F), which indicates when fog may be encountered as shown below.